Viewpoints

These Viewpoints have been created by members of the Maidenhead Neighbourhood Forum. If you would like to join the debate, please go to our Facebook page (link here) where comments are open and public. If yo would like to contribute a Viewpoint article about these topics, please send an email to viewpoints@mnf.org.uk.

1 HOW WILL WE PAY FOR INFRASTRUCTURE?

Viewpoint by Richard Davenport

As Maidenhead regenerates and grows, funding for infrastructure is vital to maintain residents’ quality of life and for the town to function smoothly. The Borough Local Plan envisages Maidenhead’s population growing by a massive c45% by 2033, much of this growth focused on the town centre.

Developers must provide their own on-site infrastructure for things like parking, shared play areas, etc. However, broader and cumulative infrastructure requirements such as schools, highways, public open spaces and community facilities are the council’s responsibility to deliver.

Under the old S106 developer contribution system, developers paid in to infrastructure ‘pots’, which the council held and then used to build say a new school, road, or leisure facility. The guideline for developer contributions then was around £12k per 2-bed flat, yielding significant funds that the council could invest in infrastructure. S106 agreements for off-site infrastructure have now been replaced by the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL), which gives RBWM more flexibility over how and when community infrastructure is provided.

CIL is a flat rate £ per M2 levy, giving clarity and certainty. Contributions from development in one part of RBWM do not have to be spent in the same area, but where a Neighbourhood Plan has been adopted local residents can influence where and which infrastructure improvements are prioritised.

Whilst the CIL system now applies across RBWM, the levy in Maidenhead Town Centre has - uniquely - been set at £0 per sq m - ostensibly to incentivise developers and help deliver growth targets. The justification for a zero CIL rate in the town centre is not in the public domain, but developers argued that they could not ‘afford’ to pay CIL if town centre developments were to be viable, due to high land values and the council’s other policy priority of affordable housing. The same pressures are pushing developers to build ever higher. While tall buildings help viability, they trigger an even greater need for accessible green and blue public open spaces and community facilities.

So how can RBWM realistically fund community infrastructure while CIL is £0 per sq m in the town centre? While S106 agreements can still be used to fund the direct infrastructure requirements of a development, the absence of CIL in the town centre means nothing goes into the wider infrastructure ‘pot’. Perhaps Windsor and Ascot will be happy to divert their CIL collections (where the levy is applied) to upgrade Maidenhead’s infrastructure… but somehow I doubt it!!

2 NICHOLSON’S: WHERE IS THE CLIMATE AGENDA?

Viewpoint by Andrew Ingram

You may or may not like the look of the Areli proposals for the town centre, but there’s a huge elephant in the room that needs to be talked about: climate change.

You may or may not like the look of the Areli proposals for the town centre, but there’s a huge elephant in the room that needs to be talked about: climate change.

In the Non-Technical Summary of the developers’ Environment Statement (para 235), they estimate that the project will generate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of 7,136 tonnes of CO2e every year for the lifetime of the project. This will be an over-estimate as it assumes the current Nicholson’s Centre emissions are zero, but either way we are talking about a LOT of harmful emissions.

The summary also says that some of the concrete from the demolition will be recycled, bring the annual emission of harmful gases down to an average of 7,119 tonnes of CO2e. That’s a 0.2% reduction. This is all that is discussed in the way of mitigating the harmful GHG emissions from the project.

I think they can do better.

And in 2020, with the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead having declared a Climate Emergency, I am very surprised they haven’t taken the subject any further.

Every industry is taking climate seriously now, and the construction industry is critical – it accounts for an estimated 40%*of all energy-related carbon emissions. There is a clear agenda for change within it, not least because, in the words of Emma Hoskyn of property specialists JLL, “we’ll start to see more occupiers only wanting to take space in net zero carbon buildings**”.

We know a lot more now about greener alternatives for construction – passive solar, greywater plumbing, green roofs etc; these are proven technologies.

And for the emissions we can’t get rid of, how about offsetting the carbon? According to N0CO2***, planting enough trees to offset the annual 7,000 tonnes of CO2e for 30+ years would cost around £180,000.

For a £400 million project. Time for some thinking.

* https://www.worldgbc.org/news-media/global-status-report-2017

3 NICHOLSON’S: HOW DOES THIS PLAN FIT WITH FUTURE HOUSING STOCK?

Viewpoint by Martin McNamee

Most interested Maidonians should be familiar with the current annual housing target of 712 new dwellings*. Of course, this figure applies to the whole RBWM area. In the last full year for which data is available, 52% of new completions were in the seven unparished wards of Maidenhead ( the area covered by Maidenhead Neighbourhood Forum - and indeed Maidenhead Civic Society.) This is where the action is, and the focus is currently on Maidenhead Town Centre.

Most interested Maidonians should be familiar with the current annual housing target of 712 new dwellings*. Of course, this figure applies to the whole RBWM area. In the last full year for which data is available, 52% of new completions were in the seven unparished wards of Maidenhead ( the area covered by Maidenhead Neighbourhood Forum - and indeed Maidenhead Civic Society.) This is where the action is, and the focus is currently on Maidenhead Town Centre.

Many residential schemes are underway in the centre of Maidenhead and they are virtually all flatted developments. Shanly Homes have three residential blocks permitted on York Road in addition to their Chapel Arches development. The Countryside / RBWM joint venture on St Ives Road and Park Street is well underway, whilst the Landing redevelopment of the King Street Triangle appears to be on hold. It is unfortunate for the Nicholsons scheme that it appears to be at the end of a planning chain that will deliver more than 2000 flats in the Town Centre.

The flatted redevelopment in the Town Centre is driven by two prime factors. Firstly and unusually there is a nil Community Infrastructure Levy, so no contribution has to be paid by developers towards infrastructure projects around the town. Secondly, flats are cheaper to build than houses, require less land and deliver unit volumes - especially when housing targets are being chased.

The consequence of this frontloading of flat building is that in the last reported year 84% of dwellings completed across the Borough were 1 and 2 bed flats. This compares with a strategic market assessment of a housing stock requiring 35% of 1 and 2 bed flats. Of course, these figures apply to the year ending March 2019 and the same RBWM report states that there was a pipeline of 1558 dwellings which had received planning permission and were not completed - or started. It can only be surmised what proportion were flats.

So the Nicholsons proposals are going to add a further 364 dwellings to the flatpile. There is a good mix of sizes ranging from studio flats to one enormous 4 bed penthouse for 8 people. All flats are of a satisfactory size and above the published minimum space guidelines. However, to deliver the number of flats to make the scheme viable it is necessary for the main residential block to rise to 25 storeys. The social and psychological aspects of high rise living are not addressed in the planning proposal. A further 364 flats equates to more than 50% of the annual target across the Royal Borough. It has to be envisaged that eventually the oversupply of flats will drive down demand and prices.

Although there appears no mention of "affordable" housing, it is a positive to see the introduction of "extra care" units for the elderly with a further 311 dwellings proposed. There will be an increasing need for such facilities with an aging population, and having such a housing option will free up traditional family homes which are currently occupied by the elderly.

- RBWM housing need has been independently assessed and will require 712 new homes every year on average to 2033

4 NICHOLSON’S: THE IMPLICATIONS FOR GETTING AROUND

Viewpoint by David Dyer

So what does the Areli planning application say about transport?

So what does the Areli planning application say about transport?

These are probably the key claims from the Executive Summary of the Transport Assessment:

- It is in an inherently sustainable location with excellent accessibility to existing and proposed public transport links, including Crossrail, as well as pedestrian and cycle networks.

- The assessment identifies that the Proposed Development will have a limited impact on the operation of the local transport networks, while significantly improving pedestrian permeability in the town centre.

Note that the first point states that it is the accessibility to transport that is said to be excellent not the actual transport itself. Specifically, the development has the advantages that it is within walking distance of the station and has bus stops nearby. Rail transport is, of course, fine for those who want to head to London, while the Elizabeth Line will improve access to the more easterly parts such as the City and Canary Wharf. Train links are also good if you want to head west to Reading, Bristol or Oxford. However, they are not available if you wish to head north to High Wycombe or south to Bracknell. It is stated in the document that there exist a range of high frequency bus services. Nevertheless, the reality is that the Royal Borough currently has the lowest usage of buses in the country. Of course, both the use and capacity of public transport has fallen dramatically in these Covid times and there is a question on how long that will continue.

Those who walk or cycle around the centre of Maidenhead may wish to comment on the description that ‘The Site has good pedestrian and cycle access with footways and cycle lanes provided in and around Maidenhead that are well lit and well maintained’.

The plan is proposing 675 new flats (to add to the 400 planned for the Landing development). There must be hope that the proposed Active Travel Plan measures such as including a walking and cycling map in travel brochures, considering setting up a Bicycle User Group, investigating the potential for discounts and training for cycling will dissuade some from owning a car. Even if occupants do not commute, they may wish to travel outside of town at weekends. At least there will be 4 car club spaces they could take advantage of. Finally if you were wondering what ‘significantly improving pedestrian permeability’ means, you will no longer will have to walk around the Nicholson’s Centre when it’s shut at night.

5 NICHOLSON’S: HOW THE FINANCING WORKS

Viewpoint by Matthew Shaw

How do you deliver a scheme costing £400 million when you don’t have anything remotely close to £400 million? How does the financing work?

Areli is backed by Tikehau Capital. The job of an asset manager like Tikehau is to find worthwhile investments for investors looking for a home for spare money. Commercial real estate is an asset “class” that Tikehau happens to specialise in.

Areli’s job is to package their scheme in such a way that it can be sold to investors. It is not about designing a scheme that is perfect for Maidenhead or the people that will live and work there; rather, it is about hitting the hot-buttons that attract the money to get it built, from people who will never visit. Tikehau’s role now is as an incubator, providing enough debt finance to Areli to acquire the site and take it through the early planning stages – where we are now.

The scheme is blocky and tall for a reason. Blocks are easily understood packages designed for sale to large investors. Investors are often based in the Far East where tall buildings are “expected”, and Rob Tincknell of Areli has 10 years’ experience of working with Malaysian investors on the Battersea scheme. Areli would probably build a lower-rise, more higgledy-piggledy scheme if that were not their target market.

Areli is already encouraging larger investors to take “options” to build whole blocks. One is believed to specialise in senior living investments, and they in turn will be looking at how they can sell on.

To move to the next stage in the financing, Areli must show that it has acquired title to the land, has outline planning consent in place and has widespread public support. (How consent is obtained could be another Viewpoint.) The scheme can fail or stall at this point if Areli is unable to convert those options into commitments – as we could be seeing with The Landing.

No-one will buy a flat from Areli. They’re not an end-to-end developer like the Shanly group. They are a financial operator, only founded in 2018, and it remains to be seen whether they choose to scale up to manage the construction – or sell the fully-financed, fully approved scheme onto a construction specialist.

Rob Tincknell is a visionary for how town centres should change. I don’t believe the financing side is what gets him up in the morning, but he has to listen to the money-folk as much as the architects when designing this scheme.

6 NICHOLSON’S: THINKING ABOUT "VISUAL IMPACT"

Viewpoint by Ian Rose

A Planning Application must clearly show the intended development in factual terms, but it often contains also a persuasive element aimed to convince the public that the development will be wholly beneficial, and to convince the planning officers that it fully conforms to Planning Policy.

A Planning Application must clearly show the intended development in factual terms, but it often contains also a persuasive element aimed to convince the public that the development will be wholly beneficial, and to convince the planning officers that it fully conforms to Planning Policy.

It is useful to read planning applications with an enquiring mind, and to evaluate the reasoning given, keeping an eye for what hasn’t been said or where different judgements could be made. For example, the reasoning for adopting the scheme proposed may seem the only logical conclusion, but it may omit alternative schemes which would be less profitable to the developer.

The images below are all taken from the Areli Planning application, and are intended to encourage informed evaluation.

Pic 1 is a simulated street scene of Broadway, roughly from the Odeon cinema, with the Landing scheme, assumed built, on the right and the proposed Nicholson Quarter on the left. It is a new place created by the developments, neither of which currently exist. The picture is chosen to show part of the skyline as well as the street level view.

What kind of feel would this street have? Is it a place you would be happy and safe?

In addition to images of new places, the Planning application contains a “Townscape, Heritage and Visual Impact Assessment” – in plain English, what it’s going to look like in the context of the existing town. Here we take a few examples.

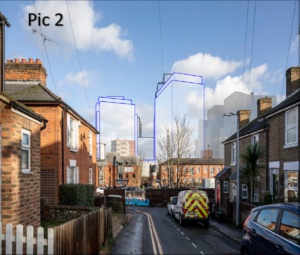

Pic 2 shows the development viewed from Albert Street to the West, with the proposed buildings in blue outline, and the consented Landing development to the right, in grey. The developer’s assessment of the magnitude of change is “Medium/High”, and the scale and nature of effect is “Moderate Beneficial (Significant)”.

Pic 2 shows the development viewed from Albert Street to the West, with the proposed buildings in blue outline, and the consented Landing development to the right, in grey. The developer’s assessment of the magnitude of change is “Medium/High”, and the scale and nature of effect is “Moderate Beneficial (Significant)”.

What do you think about the size and nature of the effect?

Pic 3 shows the development where it joins the High Street, which is a Conservation Area. The developer’s assessment is that the Proposed Development would considerably enhance the character of this view and the Conservation Area, and they assess the magnitude of change as “Medium”, with scale and nature of effect as “Moderate/Major Beneficial (Significant)”.

Pic 3 shows the development where it joins the High Street, which is a Conservation Area. The developer’s assessment is that the Proposed Development would considerably enhance the character of this view and the Conservation Area, and they assess the magnitude of change as “Medium”, with scale and nature of effect as “Moderate/Major Beneficial (Significant)”.

What do you think about the street scene around its entrance from the High Street?

The view in Pic 4 is from Castle Hill roundabout, with the Methodist Church forming the Western end of the Town Centre Conservation Area. The developer’s assessment of the magnitude of change is “High”, and the scale and nature of effect is “Moderate Neutral (Significant)”.

The view in Pic 4 is from Castle Hill roundabout, with the Methodist Church forming the Western end of the Town Centre Conservation Area. The developer’s assessment of the magnitude of change is “High”, and the scale and nature of effect is “Moderate Neutral (Significant)”.

What do you think about the change to the view, and the setting of the church and Conservation Area?

7 NICHOLSON’S: TOO TALL, TOO INTENSIVE?

Viewpoint by Judith Littlewood

In February I wrote a piece for the Forum on tall buildings (link here). This was prompted by the spate of planning applications for buildings above the maximum building height which RBWM laid down in its Tall Buildings Strategy document - the maximum in the central area is 19 storeys. The Areli application proposes one block of 25 storeys,and others ranging between 4 and 15 storeys.

In February I wrote a piece for the Forum on tall buildings (link here). This was prompted by the spate of planning applications for buildings above the maximum building height which RBWM laid down in its Tall Buildings Strategy document - the maximum in the central area is 19 storeys. The Areli application proposes one block of 25 storeys,and others ranging between 4 and 15 storeys.

Tall buildings pose design challenges such as overlooking, wind tunnel effects and reduced daylight and sunlight. They can also have a significant effect on the microclimate such as wind impact, over-shadowing, light pollution and glare. Much will depend on how successfully Areli deal with these issues to ensure that residential amenity both within the scheme and the neighbourhood is not compromised. Attractive well maintained public spaces will be central to attracting people to use the shops and cafes. Will this challenge be made more difficult by the loss of the Community Infrastructure Levy in central Maidenhead?

The Tall Buildings Strategy document produced for the Borough by the Urban Initiatives Studio states that tall buildings are less sustainable than medium rise ones. They are more resource and carbon intensive to construct and once built use more energy due to requirements for lifts, mechanical ventilation, cooling and lighting. Will Areli’s resource intensive development be in keeping with the Borough’s commitment to the climate emergency ?

The scheme will significantly add to the oversupply of small flats in Maidenhead. Young couples wanting to start a family may find it difficult to sell and move on resulting in young children living in accommodation unsuitable for their needs. Children who live below the second floor level play out more, have more friends, do better at school and are less likely to be killed falling from windows and balconies.

8 NICHOLSON’S: RESPECTING THE AREA'S HERITAGE

Viewpoint by Matthew Shaw

Levelling the Nicholson Centre and its car park gives Areli a great site in the heart of Maidenhead – but not quite a blank canvas. Vague echoes of its former history still reverberate – of the lively working community that lived there in the shadow of Nicholson’s Pineapple Brewery up to 1960, the truncated streets of White Hart Road and Brock Lane, a few survivor buildings like the bakery (now the South African Shop).

Levelling the Nicholson Centre and its car park gives Areli a great site in the heart of Maidenhead – but not quite a blank canvas. Vague echoes of its former history still reverberate – of the lively working community that lived there in the shadow of Nicholson’s Pineapple Brewery up to 1960, the truncated streets of White Hart Road and Brock Lane, a few survivor buildings like the bakery (now the South African Shop).

Areli wants to regenerate that intimate, neighbourly environment. It was run-down, a bit grungy – but was walkable, close to work, the pubs, had its little shops. They are absorbing some of that pre-concrete heritage into their plans.

The last people moved out of Moffatt Street sixty years ago. It isn’t ancient history - I have been in touch with several who are still alive. Moffatt Street was a tight community let down by its poor housing stock – and the Borough decided it would make a better car park.

Areli’s early plans were for a network of streets and lanes that, by chance, largely followed the old street pattern. As the plans developed, the old street names crept back in. Moffatt Street will be reborn; the same true for Sydenham Place – a small terrace now under the Broadway carpark. The area already had a central square – but it had no name, and Sir Nicholas Winton is the obvious person to honour anyway.

I’d have loved to see the “Pineapple” name used somewhere – maybe it still will be – but it is a motif that could be worked into the street art.

What about the brewery connection? Maidenhead was a thirsty town, with four breweries and a serious lot of pubs. Areli has proposed including a micro-brewery in the scheme and is keen to suggest a young urban social vibe might emerge. In Britain’s industrial cities, it has; Areli’s punt is that Maidenhead is ready to make the transition.

Heritage matters. Taplow Riverside includes a false waterwheel that is just naff - because rootedness in reality matters too.

Areli’s plans do recreate the street-level fundamentals. But the scheme also leans in, depending on locals, incomers, the new landlords and businesses to create a great neighbourhood.